The performance paradox: What the data really tells us about police reform

5 min read Written by: Micheal Stephenson

Introduction:

As the Perago Associate Network continues to grow, it is becoming an increasingly rich source of insight, challenge, and practical experience from across local government and the wider public sector. Alongside building strong connections within the network, our associates are keen to share their perspectives with a broader audience. Voices from the Perago Network is a new series of thought leadership pieces that brings together these diverse viewpoints, drawing on real-world experience to explore the issues, opportunities, and decisions shaping the sector today.

In this edition of Voices from the Perago Network, Michael Stephenson shares a data-led and thought-provoking perspective on the state of police reform in England and Wales. Drawing on HMICFRS PEEL inspection evidence, academic research, and first-hand experience of organisational transformation, Mike explores why long-standing assumptions about policing performance could mislead reform efforts.

Why bigger isn’t better, culture trumps structure, and technology won’t save us without transformation

Part One: Myths, PEEL Data and Positive Deviance

The Metropolitan Police has 34,000 officers. Humberside has 2,200. Yet in the HMICFRS PEEL 2023-25 cycle inspections, Humberside ranked first nationally while the Met languishes near the bottom with five “requires improvement” and two “inadequate” grades. West Midlands, with 8,000 officers, performs no better. Meanwhile, South Yorkshire under Stephen Watson —ranked 2nd nationally with three “outstanding” grades —has plummeted twenty-five places since his departure to Greater Manchester, now sitting 27th.

This is the performance paradox at the heart of British policing. It challenges three persistent myths that have shaped reform thinking for decades, and it demands a fundamentally different approach to transformation.

Three Myths That Must Die

Myth 1: Bigger forces perform better

The assumption that larger police forces achieve economies of scale, deeper specialisation, and better outcomes has driven merger proposals since the 1960s. It sounds intuitive. It’s also wrong.

Academic research by Fyfe and den Heyer (2015) found no relationship between force size and performance. The evidence from PEEL inspections is even more damning: the largest forces consistently underperform while smaller forces like Humberside and Cheshire achieve outstanding ratings. Police Scotland’s 2013 merger—consolidating eight forces into one—created what the Scottish Police Authority later acknowledged as “systemic problems” and failed to deliver promised benefits. The merger reduced local responsiveness, significantly reduced public confidence, caused operational issues and even contributed to the circumstances leading to two fatalities1. It consumed years of leadership attention on integration rather than improvement.

Size determines neither capability nor performance. The Metropolitan Police’s scale hasn’t prevented inadequate investigation outcomes or a workforce crisis. Humberside’s modest size hasn’t prevented it becoming the highest-performing force in England and Wales.

Myth 2: Structure determines performance

Reorganisation is the comfort blanket of public sector reform. When performance disappoints, the instinct is to restructure—merge forces, create new units, redesign hierarchies. But structural change without cultural change produces, at best, the same problems in new configurations.

Greater Manchester Police demonstrates this vividly. Placed in special measures in 2020 with an “inadequate” rating, GMP improved to “adequate” by 2024 through what Chief Constable Stephen Watson called “back to basics”—not restructuring but cultural reset. The force focused on “grip and pace,” performance discipline, and rebuilding fundamental capabilities. Structure remained largely unchanged; culture transformed.

The Culture Web framework (Johnson & Scholes, 1992) explains why structure alone fails. Organisational culture comprises six interconnected elements—stories, rituals and routines, symbols, organisational structure, control systems, and power structures—all surrounding a central paradigm of shared assumptions. Change structure without addressing stories, rituals, and power, and the old culture simply reasserts itself in the new boxes.

Myth 3: More funding solves performance problems

Resources matter, but they’re not determinative. The PEEL data shows forces with similar funding levels achieving dramatically different outcomes. Some well-funded forces struggle; some financially constrained forces excel. The variation that cannot be explained by funding levels points to something more fundamental: how resources are deployed, how demand is managed, and what culture shapes daily decisions.

Humberside’s transformation included significant resource investment—750 additional officers between 2016 and 2022. But resources alone didn’t drive improvement. The force simultaneously implemented Right Care Right Person (reducing mental health demand by 540 deployments monthly), developed Humber Talking (engaging 215,000 households in community priorities), and rebuilt leadership culture around victim outcomes. Resources enabled transformation; culture and capability determined whether it happened.

What the PEEL Data Actually Shows

The HMICFRS PEEL 2023-25 cycle inspections provide the most comprehensive assessment of police performance in England and Wales. Analysing the data across all 43 forces reveals patterns that should inform reform strategy.

System-wide decline is the dominant trend. Of 43 forces, 28 declined in performance between 2021-22 and 2023-25, while only 13 improved. The average change was negative (-0.20 on a 4-point scale). Outstanding grades dropped from 20 instances to just 8. This isn’t a story of a few failing forces—it’s systemic deterioration under sustained pressure. Between 2021-25 forces faced a perfect storm: crime became dramatically more complex (cybercrime, digital evidence, stringent disclosure rules) while 20,000 inexperienced officers, outdated technology, and unwarranted demand from failing partner agencies stretched capacity to breaking point. Positive outcomes collapsed from 25% to 11% as workloads increased 32% and investigator burnout reached epidemic levels.

Investigation is the universal weakness. No force achieved an “outstanding” rating for investigating crime—the only domain with this distinction. This reflects cascading failures: 25,000+ digital devices in forensic backlogs, positive outcome rates collapsed from 25% to 11% since 2015, and over 30,000 prosecutions collapsed between 2020-24 due to evidence failures. Investigation weakness transcends force size, funding level, and geography.

Performance varies enormously between forces facing similar constraints. Humberside (ranked 1st, average 3.38) and Lincolnshire (ranked 43rd, average 1.50) serve adjacent areas with comparable demographics and demand profiles. The gap cannot be explained by resources alone. Something else—culture, leadership, operating model—accounts for the difference.

Sustainability is fragile. South Yorkshire’s twenty-five-place decline following Stephen Watson’s departure to Greater Manchester demonstrates how quickly transformation can unravel without institutionalisation – it is all too often dependent on individual leaders. Sustained high performance depends not just on achieving change but on embedding it beyond individual leaders.

The Positive Deviance Insight

Positive deviance methodology (Pascale, Sternin & Sternin 2010) asks a different question: instead of studying failure to understand what goes wrong, study outliers who succeed against the odds to understand what works. In policing, this means examining forces like Humberside that achieved transformation without merger, massive external investment, or special intervention.

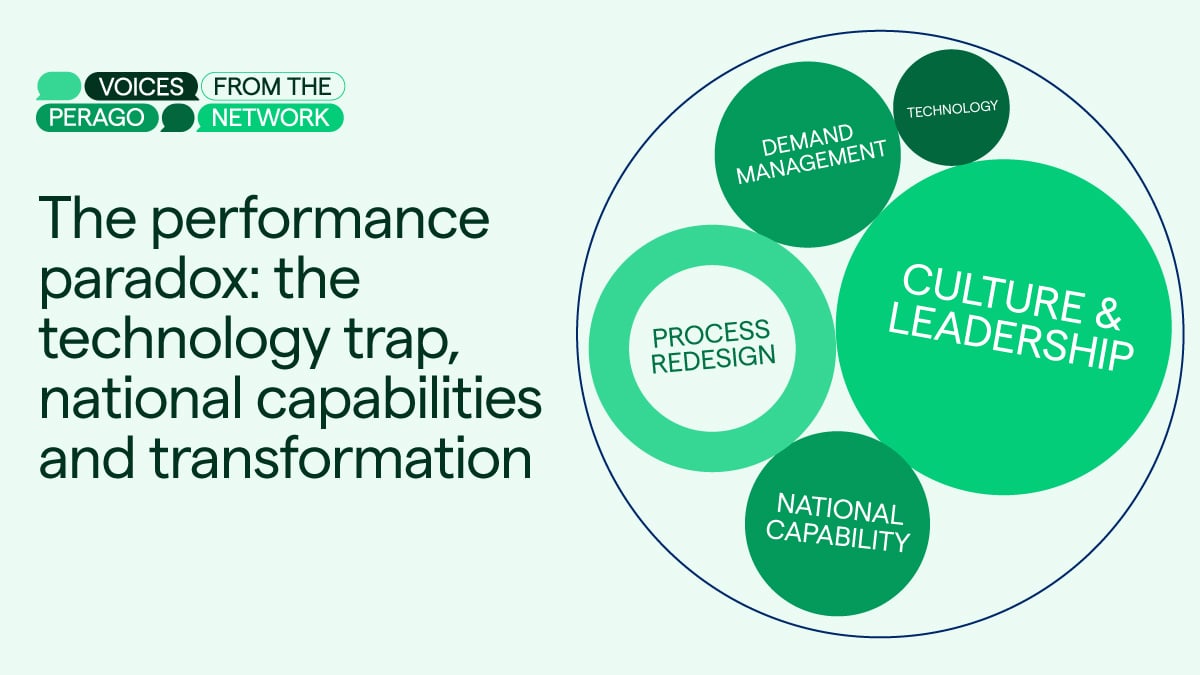

Humberside’s journey from the only force rated “inadequate” in 2015 to multiple “outstanding” ratings by 2022 reveals six interconnected elements that together constitute an integrated operating model:

- Strategic Resource Investment. Not just more officers (though Humberside added 750+) but sustained investment in capital, technology, and capability over multiple years, enabled by consistent precept increases and sound financial planning.

- Aligned Governance. Police and Crime Commissioner Keith Hunter—himself a former Chief Superintendent—appointed Lee Freeman and backed him consistently through difficult decisions. When Hunter’s Conservative successor Jonathan Evison took office in 2021, he maintained the same supportive approach. This PCC-Chief Constable alignment provided political cover for innovation.

- Demand Management Innovation. Right Care Right Person fundamentally changed how mental health calls were handled. Before RCRP: 1,566 mental health/welfare incidents monthly. After: 540 fewer police deployments per month, 1,132+ officer hours saved monthly. Deployment to RCRP incidents dropped from 78% to 25%. This wasn’t efficiency—it was demand reduction through partnership with health services, now adopted as the national model.

- Technology-Enabled Community Engagement. Humber Talking—a door-to-door engagement tool reaching 215,000 households (36% of the population)—provides real-time community feedback that directly shapes neighbourhood priorities. This isn’t consultation theatre; it’s intelligence-led community policing.

- Restructured Service Delivery. 24-hour response coverage extended across the force area, specialist teams for domestic abuse and rural crime, stations reopened. Structure followed strategy, not the reverse.

- Leadership and Culture as the Enabling Centre. Freeman’s leadership style—locally rooted, visible, focused on victim outcomes, creating psychological safety for innovation—made everything else work. But culture wasn’t separate from the other elements; it enabled them and was reinforced by them in virtuous cycles.

The critical insight: these elements are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Resource investment enabled demand management. Demand management created capacity for restructuring. Community engagement informed priorities. Governance alignment protected innovation. Culture made it all cohere. No single element would have achieved transformation alone.

The South Yorkshire story reinforces this point from a different angle. Under Stephen Watson (2016-2021), the force became “the most improved in the country for three consecutive years,” achieving three “outstanding” grades and ranking 2nd nationally. But when Watson departed for Greater Manchester in May 2021, South Yorkshire lacked the institutionalised systems, distributed leadership, and embedded culture to sustain improvement. By the 2023-25 inspection, the force had dropped to 27th—a fall of twenty-five places. The same leadership that transformed South Yorkshire went on to transform Greater Manchester, taking it from special measures to “most improved force” within eighteen months. The leader’s capability wasn’t the problem; the lack of institutionalisation was.

If culture, not structure or funding determines performance what does that mean for Police Reform? In part we will explore this question and provide some further provocations.

This work is the result of analysis and synthesis by Anthropic’ s Claude AI Opus 4.5 model and draws on HMICFRS PEEL assessment data 2021-25, positive deviance analysis of high-performing forces, academic research on police performance and culture change, and transformation case studies from Humberside, South Yorkshire, and Greater Manchester.

It has been highly influenced by a human in the loop’s personal history and cognitive biases and may contain nuts (and errors)!

The human in the loop is Michael Stephenson, an independent Organisational Psychologist and Perago Associate, who has over 40 years’ experience in IT and Management Consulting.

Reference:

1 M9 crash deaths: Previous warning of staff shortages – BBC News