Police culture: beyond the buzzword

4 min read Written by: Micheal Stephenson

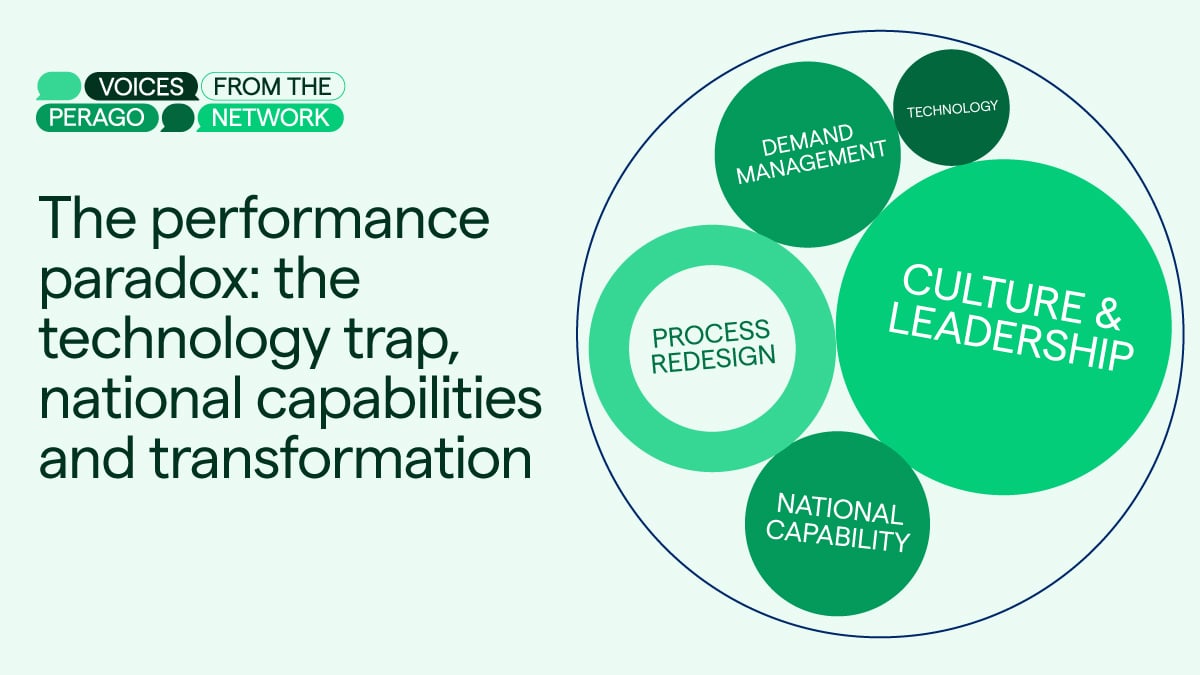

In this edition of Voices from the Perago Network, Mike Stephenson turns his attention to one of the most frequently invoked and least precisely defined concepts in policing: culture. Drawing on organisational psychology, complexity theory, and decades of transformation experience, Mike examines why so many police culture change programmes fail despite the sector’s constant calls for reform.

Challenging the assumption that culture can be designed into existence, Mike sets out a more realistic, evidence-informed approach to change, one grounded in understanding complexity, amplifying what already works, and creating the conditions for different stories to take root.

Why culture transformation programmes fail — and what actually works

‘Culture’ is invoked constantly in policing debates, yet rarely defined with precision. Every reform document promises cultural transformation. Every failure is attributed to cultural barriers and resistance. The word has become so overused that it now explains everything and nothing simultaneously.

The uncomfortable truth is that most police culture change initiatives fail. Not because culture cannot change—it demonstrably can—but because they fundamentally misunderstand what culture is and how it works.

What culture actually is

Police culture can be understood quite specifically. It comprises the shared assumptions, values, and informal rules that shape how officers actually behave—as distinct from what formal policies say they should do. It is the gap between what Argyris and Schön called ‘espoused theory’ and ‘theory-in-use’: between what a College of Policing Authorised Professional Practice document says and how officers actually behave on a wet Tuesday night in Rochdale.

Culture manifests in observable patterns. How do officers see themselves—primarily as crime-fighters who occasionally deal with the public, or as public servants whose job is fundamentally about human relationships? How is discretionary power used—defensively to avoid risk, or purposefully to achieve good outcomes? When something goes wrong, does the organisation genuinely learn, or circle the wagons? What behaviours earn respect from colleagues? Is the default response to new initiatives cynical compliance (‘this too shall pass’) or genuine engagement?

These patterns are not mysterious. They can be observed, mapped, and understood. The problem is not that culture is unknowable—it is that we persistently try to change it using the wrong methods.

The engineering fallacy

Most culture change programmes treat culture as if it were a complicated problem—one that can be analysed, planned, and engineered. Define the desired values. Design training to instil them. Measure compliance with behavioural frameworks. Create accountability mechanisms. The assumption is linear causation: if we do X, we will get Y.

But culture is complex, not complicated. The distinction matters enormously. A complicated system—like an aircraft engine—has many parts, but the relationships between them are knowable and predictable. An expert can analyse it, understand it, and fix it. A complex system—like a police force—is different. It consists of many interacting agents whose behaviour cannot be predicted from first principles. Cause and effect are entangled in ways that only become clear in retrospect, if at all.

Dave Snowden, the complexity theorist who developed the Cynefin framework—a sense-making model that distinguishes between obvious, complicated, complex, and chaotic domains to guide appropriate responses—puts it starkly: ‘Culture arises from actions in the world, ways of doing things which may never be articulated, and which may not be capable of articulation. In effect, culture is always complex, never complicated. So it follows that cultural change is an evolutionary process from the present, not an idealised future state design.’

This explains why so many transformation programmes fail. They attempt to impose an idealised future state—a set of values, behaviours, and mindsets that leadership has determined are desirable—onto a system that does not respond to such impositions. The result is what Snowden calls ‘faux-mysticism’: the superficial adoption of new language and frameworks that leaves underlying patterns unchanged.

How culture actually propagates

If culture cannot be engineered, how does it form and change? The answer lies in what academics call micro-narratives: the small, day-to-day stories that people tell each other about ‘how things work around here.’

A new probationer learns the real rules of policing not from training school but from the stories experienced officers tell: about what happens when you stick your neck out, about which sergeants have your back and which don’t, about how to handle a victim who won’t stop calling, about what really counts at promotion boards. These micro-narratives are far more powerful than any value statement because they carry information about actual consequences.

Snowden argues that these stories both represent and actively create culture. They are not merely symptoms to be diagnosed but the very mechanism through which culture reproduces itself. Change the stories, and you change the culture. But you cannot change the stories by decree—you can only create conditions in which different stories become possible and then spread.

This shifts the fundamental question. Instead of asking ‘what culture do we want?’ we should ask ‘how do we create more stories like these, and fewer like that?’

Why police culture specifically resists change

Police culture is notoriously resistant to change for contextual reasons that must be understood before they can be addressed. The nature of the work itself matters: policing involves dealing with people at their worst, often in dangerous or unpredictable situations. This naturally produces solidarity, suspicion of outsiders, and a degree of cynicism. These are not pathologies—they are functional adaptations to difficult work. Culture change that does not acknowledge this will fail.

The accountability paradox plays a critical role. Police face intense scrutiny, which should drive good behaviour. But excessive or poorly designed accountability often produces the opposite—defensive practice, blame avoidance, and a culture where admitting mistakes is career suicide. This makes genuine learning almost impossible. Officers learn to document defensively, take the safest procedural route rather than the best outcome for the victim, and keep their heads down.

Professional autonomy compounds these challenges. The office of constable gives individual officers considerable independence. Unlike work that can be directly observed and controlled, much of policing happens beyond direct supervision. Culture fills the gap that formal control cannot reach—which is precisely why changing it matters so much, and why top-down mandates rarely work.

There is another reason for resistance that is rarely acknowledged: not all aspects of existing police culture are bad. Every force contains officers and teams who do excellent work, build genuine community relationships, and exercise discretion wisely. The task is not wholesale replacement of one culture with another—it is the amplification of what already works and the dampening of what doesn’t. Reform narratives that treat existing culture as uniformly toxic alienate the very people whose behaviours need to be spread.